Jade Johnson

For International Day of the World's Indigenous People, we hope you enjoy a piece by our Graphic and Motion Designer, Jade Johnson, a team member of Indigenous Taiwanese and British descent, and a member of the Amis tribe.

“We are Amis. We dance with the sky behind us and the grass beneath our feet.”

My Ina (Mother)

Illustration of my Mother Age 20 dancing in Taitung, Taiwan.

Joy as resistance, joy without a spectator, joy with the Earth, this is what it means for me to be indigenous.

My family is part of the Amis tribe, one of the 16 recognised indigenous tribes from Taiwan. Ilisin is my tribe's annual harvest festival, one of our last surviving traditions as an indigenous people of Taiwan. It occurs this time of the year when the rice paddies are golden. Families come home to the villages to celebrate the rice harvest in the ways our ancestors have always done - by singing and dancing.

As Amis people our knowledge is embodied within us; we preserve our traditions through oral storytelling and intergenerational practice. This means that the only written documentation of our culture comes from non-indigenous archaeologists. As a result, the seeds of colonisation are so internalised in our culture that our own matu’asay (elders) become the mouthpieces of a colonial fantasy of our traditions - because what else do we have?

When you search up “Amis Harvest Festival Taiwan”, you will find multiple tourist events to experience, “authentic indigenous culture”, and various articles detailing the specific traditions and rituals that occur in these festivals. In reality, these differ village by village, and with Amis villages stretching over the east coast and central mountain range of Taiwan, there is no one way, no right way, to celebrate our Ilisin.

Growing up and living in the UK, my earliest memories of harvest festivals were when we went to Taiwan as a family during the summer holidays. Since my village was my only frame of reference for Taiwan, I used to think that every Taiwanese person celebrated the harvest festival; to me being indigenous was simply being Taiwanese. It was only when I was older, had explored the more urban areas of Taiwan, and had learnt that indigenous people make up only 3% of the Taiwanese population, that I realised how truly special these festivals are. However when preparing for this post, I felt such a profound sense of disconnect reading online accounts of harvest festivals rituals. Has my village never done this right, or has my limitation of Amis language created an insurmountable barrier to my understanding of my culture?

I called my Grandmother, a handicraft teacher of traditional craft in my village, who in her youth was one of the main organisers of my village’s harvest festival.

“Ama, what do we do in our Ilisin?”

“We sing, we dance - we celebrate a year of harvest!”

“But is that it? Aside from singing and dancing, what else do we do?”

“That’s it.”

I realised as I was questioning her I was trying to manipulate the conversation with targeted questions, desperately searching for more meaning, but failing to realise the beauty is the simplicity.

This is it, there is no hidden spirituality.

For our family, joy is our culture, to sing is our culture, to dance is our culture. My friend told me that our language is song - you cannot speak Amis without singing. When I sing with my Grandmother, it's as if we are one voice coming from two mouths, a language of care and patience, defined by generations of love. When I dance, people often ask me where I learnt how to dance the way I do. I always reply, jokingly, “It’s because I’m indigenous,” but in my heart I know this rings true.

The songs we sing at our harvest festival have no lyrics and consist only of melodic chants. On the call with my Grandmother, she told me that even though the chants have no meaning, the singer can “create their own meaning” by adding their own lyrics to the melody of the chant.

My Grandfather would always be the lead singer in my village's harvest festival. The last harvest festival I attended was the first one after COVID and also my first one within the last 10 years. My Grandfather was very ill at this time, and I remember one of the last things he told me is that he wanted me to hear him sing at the harvest festival. His condition worsened and he wasn’t able to sing at Ilisin, and he passed a week later after the festival. My Grandfather taught me how to sing, and his voice lives on in me. When I sing, I am never alone.

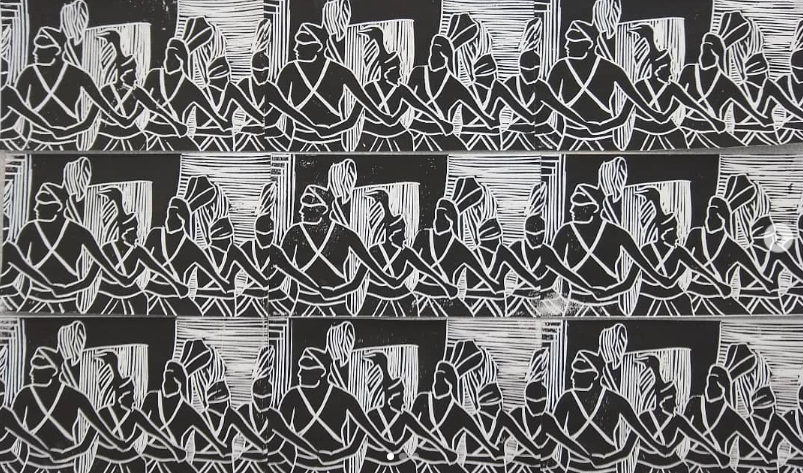

When we dance at our harvest festival, we interlink our arms together, similar to weaving. We create a unified circle that breathes and ebbs with each step we take. The most beautiful part of this is that the dancing circle never closes, always an open invitation for someone else to join.

"Ilisin, 2020, Lino Print, Jade Johnson"

The way we dance is reflected in the way we craft.

My Grandmother taught me how to make traditional fishing nets using Amis knitting - each knot is knotted individually, and this is excruciatingly time-consuming. The intention is that if the net breaks in one area, the wider net will not unravel. In this sense, each knot is important as an individual anchor but also as a small part of a wider whole. We practice sustainability within our culture through the longevity of our craft, and our intentional slowness is for the sake of preservation.

Being of mixed British and Indigenous Taiwanese heritage, I find myself negotiating cultural expectations in a Western society. I grapple with the pressure to conform to stereotypical or romanticized notions of my culture, as if my authenticity is measured by how well I embody these external ideals.

I’ve come to realise that as important as traditions are, what is true and real are my family, my friends, and myself. We define what it means to be indigenous, every single day - because we simply are. To document your own history, to become stewards of your own knowledge reproduction, is a form of decolonisation.

Mihumisang: "Are you still breathing, are you still alive?"

This is the Bunun (a neighbouring tribe to the Amis) way of greeting each other. For me, it is a constant reminder that as indigenous people, we are still here, we are still breathing, and we will be heard.

Art is my way of responding to the world - I create as a way of understanding, I create to document the humanity of the unseen. After spending the better part of 2 years living with my Grandparents in our village, Chishang, I was motivated by a sense of urgency to document and learn our traditional handcrafts that would have otherwise been lost with my Grandmother.

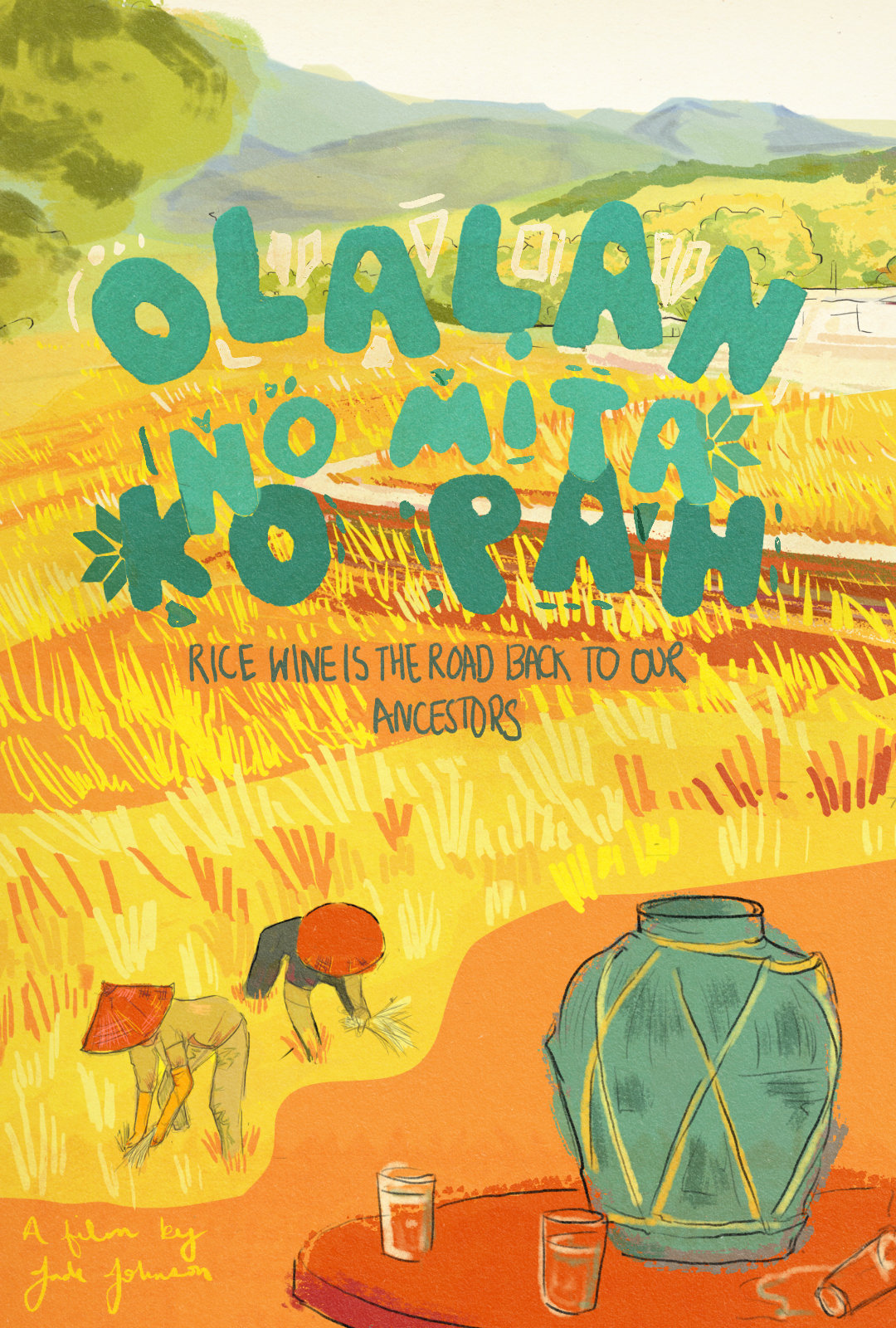

'Olalan no Mita Ko Pah - Rice Wine is the Way Back to our Ancestors' is a hybrid animated documentary directed by myself as a response to this.

“Guided by her Grandmother Anaw, a former indigenous handicraft teacher, we follow Jade as she carves a path of reconnection to her indigenous culture. Using rice wine making as a vessel for this, Jade discovers Amis peoples intrinsic connection with the land- transcendent of physical ties. The time we have with our elders is fleeting. This short film captures the importance of these moments, but also how tangible cultural practices and the cyclical nature of learning can keep us connected with our loved ones. When we drink wine, we are together.”

You can view the documentary here: https://www.taiwanplus.com/shows/culture/taiwan-pitch/230217051/olalan-no-mita-ko-pah-rice-wine-is-the-road-back-to-our-ancestors

Anu mapatay’ay kaku, hama’an tumayi,

itila yi falius, itila yi liyal

When I die don’t cry, I am in the wind,

I am by the sea- an Amis elder

Everything I do is about my indigenous heritage: my artwork, my love, my voice and my tears. All so that when I too am inevitably lost to the wind and the sea, I will leave a tangible connection to our culture for future generations to come.